IN THE MASTER’S SHADOW: Epic Fantasy in the Post-Tolkien World

“A single dream is more powerful than a thousand realities.” –J.R.R. Tolkien

“A single dream is more powerful than a thousand realities.” –J.R.R. Tolkien

Everybody’s talking about Tolkien again.

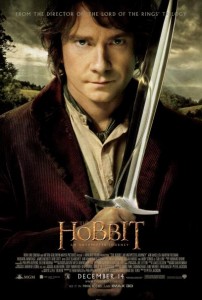

Peter Jackson’s rollicking adaptation of The Hobbit recently debuted as the world’s #1 movie, eleven years after his first Tolkien-inspired film. Much has been made of Jackson’s decision to expand the one-volume Hobbit into three movies in the tradition of the Lord of the Rings. Fans and critics argue about the wisdom of stretching this one book (itself a prequel) across three films. Yet any discussion of these movies inevitably leads back to the books themselves. And the book is always better than the movie.

J.R.R. Tolkien is to epic fantasy what Jimi Hendrix is to rock guitar; what Edgar Allan Poe is to horror stories; what William Shakespeare is to drama. It is impossible to write an epic fantasy without being somehow influenced (directly or indirectly) by the work of Tolkien. The man did not necessarily invent the fantasy genre, but he did create the modern conception of what epic fantasy looks and feels like.

After Tolkien, any book featuring elves, dwarves, hobbits, and/or goblins was borrowing elements of his work (or accused of “stealing” them outright). The trilogy became the dominant fantasy format. Even the simple orc has become a hugely popular monster, featured in novels, movies, comics, and games to a degree that Tolkien would never have expected. Tolkien’s imitators are legion, and used bookstores are full of novels written “in the tradition of Lord of the Rings.” This has been the state of the fantasy genre for decades.

Yet does Tolkien hold the “copyright” on the epic fantasy concept? How does a modern writer craft an epic fantasy that goes beyond the Tolkien paradigm and explores new ground, without simply remixing and reinventing what The Master has done?

It has been said that “there are no new stories, just new ways to tell them.” This is the job of today’s writer of epic fantasy: To tell a mythic story in some new way.

Fantasy tropes, plots, and devices are recycled endlessly, and that’s only to be expected. Fantasy fiction is the modern equivalent of the myth cycles of early humanity. The heroes, conflicts, and adventures touch on the timeless themes that run through all literature, from Beowulf to The Odyssey, all the way to Lord of the Rings and modern fantasy epics like George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire.

In The Books of the Shaper series I set out to create a world that I would enjoy exploring throughout the course of an epic-length novel and beyond. I knew right away that I didn’t want any of the more commonly used elements of “Tolkien-style fantasy”—no elves, no dwarves, no orcs or goblins. These elements (races) are so quintessentially Tolkien that I had no interest in doing “my version” of them. I love Tolkien, but I didn’t want to be him. I wanted to be myself.

Granted, Tolkien was not the first human being to write about elves or goblins or dwarves. Yet he popularized his personal vision of these creatures to such a towering degree that his take on them has largely replaced the actual folklore that birthed them. There are many writers who are entirely comfortable using elves and similar fantasy creatures in their work—and there is nothing wrong with that in principle. However, when a writer chooses to work with these popular elements he has to leap an extra hurdle of creativity to avoid accusations of “ripping off” Tolkien. Ironically, nobody accuses Tolkien of “stealing” generations of folktales, Nordic legends, and European myth-histories—the actual raw material that inspired his works. Perhaps this is because Tolkien was borrowing from uncounted sources drawn from the depths of time, rather than taking his cue from a single influence.