Ken MacLeod’s DESCENT is an alien abduction story for the twenty-first century set in Scotland’s near-future, a novel about what happens when conspiracy theorists take on Big Brother. It comes out in paperback this week, and we asked Ken what is is about Scotland that brings him, and other writers, back to it as a science fiction setting again and again.

Two months ago, Scotland was in what Charles Stross called ‘The Scottish Political Singularity’. The referendum made the entire political future so uncertain that even planning a near-future novel set in the UK had become impossible – not least because you couldn’t be sure there would still be a UK to set it in.

My novel Descent, just out in paperback, was written before the result looked close, but I was careful to leave the outcome of the then future referendum open to interpretation. In earlier novels such as The Night Sessions and Intrusion, I’ve also left it up to the reader to decide if the future Scotlands described are independent or not.

Preparing for a recent discussion on ‘Imagining Future Scotlands’ I realised that the majority of my novels are at least partly set in Scotland, or have protagonists whose sometimes far-flung adventures begin in Scotland. And it made me wonder why there haven’t been more. With its sharply varied landscape, turbulent history, and the complex, cross-cutting divisions of national and personal character which Scottish literature has so often explored, Scotland may inspire writers of SF, but as a location it features more often in fantasy.

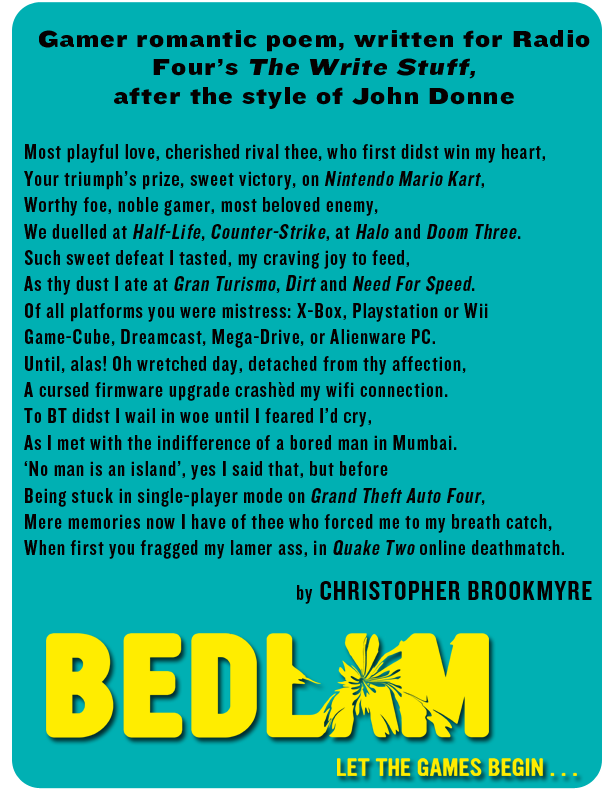

The result is that there have been many Scottish writers of SF – including Orbit’s very own Michael Cobley, Charles Stross, and the late and much missed Iain M. Banks – but not many SF novels have been set in Scotland. Of those that are, quite a few are written from outside the genre, such as Michel Faber’s Under the Skin. Flying even more cleverly under the genre radar, Christopher Brookmyre has been writing what amounts to an alternate or secret history of contemporary Scotland – some of them, such as Pandaemonium, with SF or fantasy elements – for two decades. And within the genre, there are some well-regarded novels I haven’t read, notably Chris Boyce’s Brainfix. I can’t help feeling I’ve missed stacks of obvious books. If so, I look forward to being corrected in the comments.

Let’s start with straight, unarguable genre SF.

Halting State by Charles Stross is a police procedural set in a near-future independent Scottish republic. Unlike many fictional detectives, the heroine is married, and her wife understands her. The multi-viewpoint second-person narration, though disorienting at first, soon becomes transparent – you could say you get used to it – and apt for a novel set partly in a Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Game. From the opening shots of a bank robbery in virtual reality, the story has you under arrest and briskly frogmarched along.

Time-Slip by Graham Dunstan Martin is a much grimmer vision of a future Scotland. Decades after a nuclear war, the Scottish Kirk has resumed its dour dominance of society. Our sympathy for the hero, a young heretic who founds a new religious movement on his rediscovery of the Many Worlds Interpretation of quantum mechanics, fades as the implications sink in. It’s a thought-through and engaging novel, sadly out of print, but easily available secondhand.

Not quite SF, but set in a (then) future with a deft touch or two of technological extrapolation, the political thriller Scotch on the Rocks is an old-school Tory take on an armed insurrection for Scottish independence. Sex and violence are never far away. Glasgow gangs and Moscow gold play a bit part behind the scenes. Given that it was written by Douglas Hurd and Andrew Osmond, this isn’t surprising. What is surprising is the sharpness of its insight into the issues that drive the independence movement, from cultural alienation through economic decline to nukes on the Clyde. The speeches, give or take the odd detail, could have been delivered this September.

Moving to fantasy, Alasdair Gray’s Lanark is often rightly cited as a landmark in Scottish literature. It was an avowed influence on Iain Banks’s The Bridge, the closest Iain ever came to writing SF set in Scotland. But my own favourite of Gray’s novels is Poor Things, a Scottish revisioning of Frankenstein that confronts the poor creature with the harsh self-confidence of the Victorian age and that age with her outraged innocence.

Michael Scott Rohan’s science-fantasy novel Chase the Morning starts in Scotland – or at least in a port very like Leith – and casts off for worlds unknown on an endless ocean, full of adventure and romance. Its striking image of the Spiral, in which ships magically sail upward beyond the horizon to farther seas in the sky, was inspired by the vista down the Firth of Forth. On some evenings looking down the Firth you can’t tell where the sea ends and the sky begins, or what’s a cloud and what’s an island. Like all good science fiction and fantasy, this novel and its sequels make us see the real world in a different light.

Finally, we shouldn’t forget Scotland’s abiding presence in the wider field: Victor Frankenstein built the mate for his creature on a remote Orkney island; the Mars mission that opens Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land had as its prime contractor the University of Edinburgh; and Star Trek‘s engineer Scotty was born in Linlithgow . . . a few miles from Scotland’s notorious UFO hotspot, Bonnybridge.