We remember when urban fantasy first arrived on our shelves, but the genre has changed significantly since then. Are these stories still popular? If so, why? We asked some of Orbit’s authors for their take on the genre’s past, present and future.

Where does urban or contemporary fantasy come from?

JIM BUTCHER, author of the bestselling Dresden Files, as well as recent adventure fantasy THE AERONAUT’S WINDLASS

‘Urban fantasy is nothing more or less than the resurgence of fairy tales. We’ve changed what our big bad wolves look and act like, and our forests appear somewhat different than they used to, and Little Red Riding Hood is generally much more heavily armed than she has traditionally been, but we’re telling the same stories, in the same ways, with the same emphasis on the fantastic and the terror and delight of its clash with our everyday world.

It’s the everyday reality that so many of us find terrifying – to such a degree that we flee to tales of vampires and werewolves and dark sorcerers just to lighten the mood.’

CHARLIE FLETCHER, author of THE OVERSIGHT and THE PARADOX

‘People have always created stories to try and make sense of stuff they could neither see nor understand. ‘Urban’ fantasy is just a logical step since as society has become less rural and more metropolitan so the old dark woods of the old fairy-stories have been replaced by a sodium-lit concrete jungle. And of course we may have moved to the cities, but we brought our darkness with us.

There’s a lot of product jammed in under the urban fantasy label that doesn’t do it for me, but the books that do mean something to me are the ones that engage creatively with the inevitable transition from the old to the new world and deal with its consequences as a central part of the story (AMERICAN GODS by Neil Gaiman is a particularly fine and definitive example of this).’

What does the future of urban fantasy look like?

LILITH SAINTCROW, author of the Bannon and Clare Affairs and BLOOD CALL, as well as many other urban fantasy series

‘I think the last five years, as with any shiny new trend, have brought a certain amount of reader fatigue. Urban fantasy isn’t going away, but it’s not so much of a Wild West ‘let’s throw a vampire in there and hope it sticks!’ anymore. Which is very good, if sometimes frustrating when paranormal or urban fantasy is what you want to write.

After working in publishing for so long, I see “urban fantasy” as a genre title, nothing less, nothing more. There’s always a market for tales well told, and urban fantasy, like any genre, offers a set of tools and toys for a writer to play with.’

BENEDICT JACKA, author of the Alex Verus novels

‘I’d have trouble pinning down exactly how urban fantasy’s changed over the last five years, but I’m pretty sure that it’ll stay popular for the foreseeable future. The mash-up nature of urban fantasy lets it evolve easily, and the sources it draws on (comic books, games, epic fantasy) still have a lot of resonance for city-dwellers. So while I’d expect the type of urban fantasy stories to shift over time, I think the genre will stick around for a good while yet.’

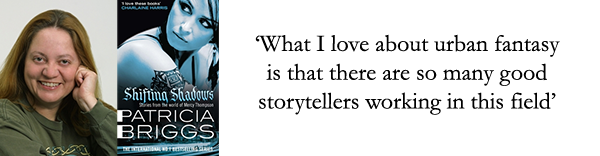

PATRICIA BRIGGS, author of the Mercy Thompson series and the Alpha and Omega series

‘There isn’t a reader appetite for urban fantasy the way there used to be. Five years ago, any book that was urban fantasy was guaranteed a certain number of readers. I think, and it is not a bad thing, that readers are pickier now. For me as a reader, right now, what I love about urban fantasy is that there are so many good storytellers working in this field. Good stories still work and can still find an audience, though it might take longer to find a readership than before.

One of the things that I actually like about this is that we are seeing more diversity in books that are published again. I love, love, urban fantasy. But I also love space opera, traditional fantasy, and contemporary fantasy – and those genres were getting drowned.’

ELLIOTT JAMES, author of CHARMING

‘I like to read stories where the extra-ordinary and the ordinary mingle. Some people sneer at escapist literature, but “escape” implies relief, release, and freedom, none of which are bad things. Escape also inevitably holds a mirror up to the thing being escaped from.

Urban fantasy often gives ordinary characters a chance to demonstrate extraordinary qualities. It encourages readers to examine what it means to be human through contrast or by eliminating a lot of the obvious assumptions.

There have always been stories that introduced fantastical otherworldly elements into the everyday knockabout world that we humans optimistically call reality, and I expect there always will be.’