Scott Lynch & Matthew Stover on THE REPUBLIC OF THIEVES and ACTS OF CAINE

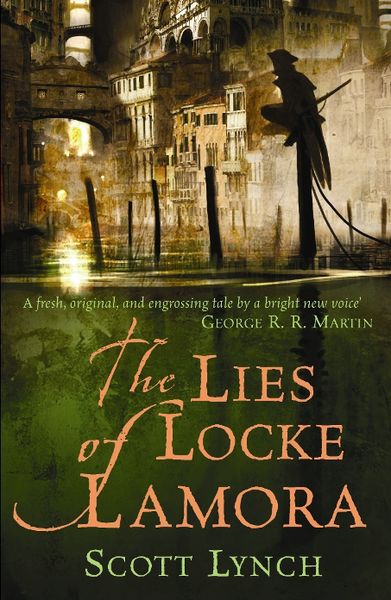

Scott Lynch: volunteer firefighter, powerful Jedi, author of The Lies of Locke Lamora and the upcoming The Republic of Thieves, all round man of letters and certainly a Gentleman, not a Bastard . . .

Scott Lynch: volunteer firefighter, powerful Jedi, author of The Lies of Locke Lamora and the upcoming The Republic of Thieves, all round man of letters and certainly a Gentleman, not a Bastard . . .

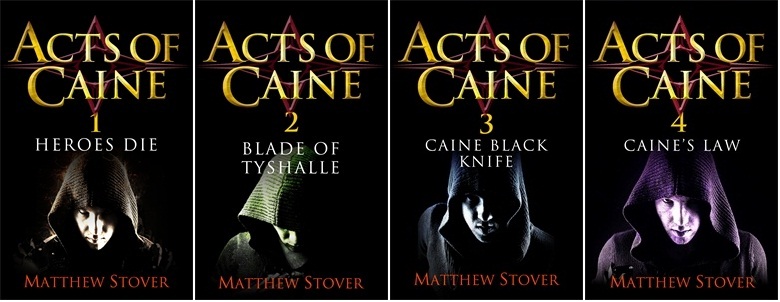

Matthew Stover: learned student of arcane martial arts, competitive drinker, author of the “heaping plate of kickass kickassery” that are the Acts of Caine fantasy novels . . . and also a very powerful Jedi . . .

Matthew Stover: learned student of arcane martial arts, competitive drinker, author of the “heaping plate of kickass kickassery” that are the Acts of Caine fantasy novels . . . and also a very powerful Jedi . . .

SO WHAT HAPPENS WHEN THESE MIGHTY FORCES COLLIDE?!

Read on to find out!

Matthew Stover: Okay, first: how soon can I get an ARC of The Republic of Thieves?

Scott Lynch: Be down at Pier 36 at midnight. Look for a man with a copy of yesterday’s Beijing Times under his arm. Offer him a cigarette. If he declines, say “Which way was the dolphin swimming?” Then follow his directions precisely. Bring a flashlight and a set of hip waders. Good luck and godspeed.

MS: Despite the first Gentlemen Bastards novel being titled The Lies of Locke Lamora, it seems to me that Locke and Jean are dual protagonists, true partners rather than hero and sidekick. While this is not unusual in other genres (especially police procedurals, for example), in ours they’re pretty thin on the ground. The only truly legendary fantasy dual-protags that spring instantly to mind are Fafhrd & the Gray Mouser, and they are explicitly portrayed as linked by mythic destiny (“Two halves of a greater hero.”) Locke and Jean, by contrast, are bound by human friendship and deep loyalty – more Butch & Sundance than F&GM.

So I’d like to get your thoughts on what inspired their relationship, and why you chose to write them this way. Were they always to be dual protags? Did Jean start as a sidekick and grow in the writing? Is there something about their friendship that has Super Story Powers?

SL: You’re making me peer back through the hazy mists of memory, man. But the honest truth is that Jean was decidedly a less fleshed-out character, initially, very much vanishing into the ensemble. His role grew in the telling, until I realized that he wasn’t just a foil for Locke but the essential foil. I grasped the benefit of having a sort of external conscience for him, another intimate perspective on Locke that would enable me to sort of hover nearby without peeling back too many layers of his mentation. For all that he’s the protagonist, we don’t spend too much time with unfettered omniscient access to Locke’s thoughts in that first novel; I wanted to express his feelings more through his actions and the responses of those around him than by writing something like, “Locke was sad now.” (more…)

When I was told that Orbit Books was releasing the entire Acts of Caine series in the UK, I let out a cheer. I am, unapologetically, a huge fan of this series of books, full as they are of action, adventure and grippingly written violence – along with classic dystopian themes, observantly written (and massively, compellingly flawed) characters, and world-building I’m jealous of as a writer even as I’m impressed with it as a reader. This is the series that put its author Matthew Stover on my map as someone whose books I had to read, no matter what he was writing.

When I was told that Orbit Books was releasing the entire Acts of Caine series in the UK, I let out a cheer. I am, unapologetically, a huge fan of this series of books, full as they are of action, adventure and grippingly written violence – along with classic dystopian themes, observantly written (and massively, compellingly flawed) characters, and world-building I’m jealous of as a writer even as I’m impressed with it as a reader. This is the series that put its author Matthew Stover on my map as someone whose books I had to read, no matter what he was writing.