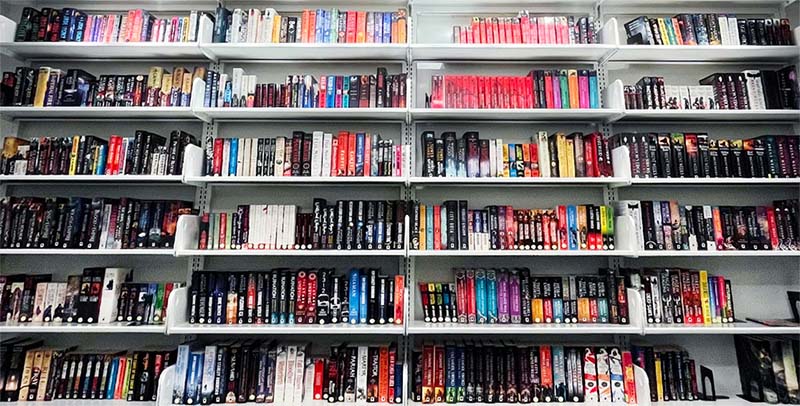

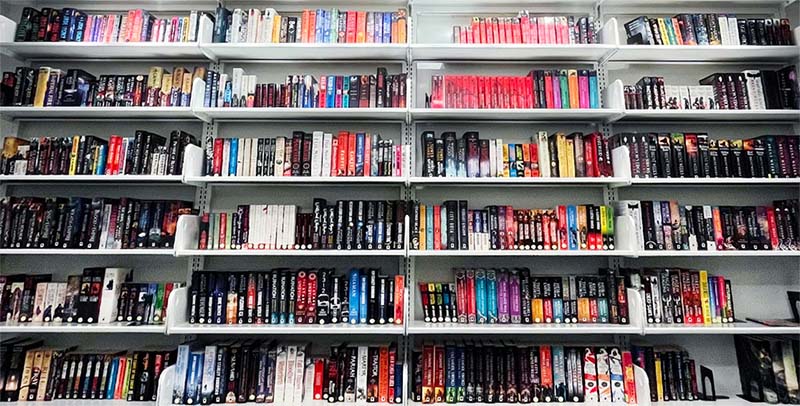

Orbit – Welcome

Welcome

Orbit publishes in the US and the UK.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

Orbit publishes in the US and the UK.