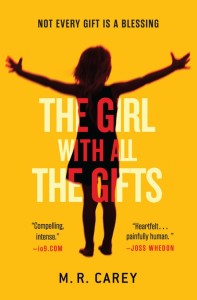

On the road with THE GIRL WITH ALL THE GIFTS

THE GIRL WITH ALL THE GIFTS releases today in the US in hardcover, and will be out in paperback in the UK next week in (June 19th). Read the first ten chapters on Facebook or listen to a sample from the audiobook.

We know you’ll be hooked by Melanie’s heart-stopping story. M.R. Carey joins us today to tell you more about that journey.

…

I don’t know why I ended up writing a road movie. I almost never watch them.

I’ll make some exceptions to that blanket statement. I love Sideways. And Midnight Run. And if we’re counting yellow brick road movies, The Wizard of Oz is pretty damn cool.

It’s just that I’ve seen so many features where changing the scenery stands in for any kind of thought-through development in either the characters or the plot. Stories where it really is just one damn thing after another, episodes piled on episodes until you get to a slightly bigger episode that you realise (after the credits roll) must have been the climax.

If you’re still with me, you’re probably already compiling your own mental list of great road movies. “Hey, fool, you forgot O Brother Where Art Thou, Easy Rider, Wild At Heart…” And yeah, I did. For the sake of my argument, I’m willing to overlook a certain amount of inconvenient evidence.

Can we agree on one thing? When you take a story that depends on a fixed setting and works well within that setting, and for no reason other than variety being the spice of life you wilfully take it out on the road, you’re flirting with disaster. The very phrase “jumping the shark”, after all, comes from that terrible Happy Days episode where the whole gang goes off to Los Angeles and hangs out on a beach.

A long while back I read an essay by the French media guru Roland Barthes in which he talked about the appeal of utopias in fiction. Barthes claimed that most utopias are finite, enclosed spaces – “idealised caves” – that satisfy our need for security by providing an environment where stability is absolute and guaranteed. He made it clear, though, that this enclosure didn’t have to be a physical thing. The classic sit-com, he argued, is utopian because it presents situations and relationships that are entirely resistant to change. One of his favourite examples of a utopian world was that of the Carry On movies, the mildly smutty British comedies of the 60s and 70s in which a cast of beloved character actors would mount a series of gag sketches in a historical setting, effectively playing the same roles no matter whether we were in Cleopatra’s Egypt, the Khyber Pass or the London of Jack the Ripper.

If this is true – if utopias are mostly enclosed and stable – maybe it follows that the road movie works well for dystopias, stories in which the world is going to hell in a handcart and the characters are mostly going with it. And once you start thinking about it, examples pile up. Let’s start with the most obvious – Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, whose very title proclaims its lineage. The father and son in the novel keep moving because there’s no safe place to stand still. They live in a world in which food is so scarce it’s almost non-existent, and most of their lives is spent in scavenging. The road is the symbol of a journey that never ends to a sanctuary that can’t be found. “How long were you on the road? I was always on the road. You cant stay in one place. How do you live? I just keep going.”

28 Days Later does the same thing in a different medium, and with a different apocalypse. Okay, maybe not exactly the same: when Cillian Murphy and his not-so-happy band of pilgrims leave London they do think they’re heading for a sanctuary – an enclave of humans who have an answer to the zombie plague and can offer protection from the infected. But the journey is a hellish war of attrition and the destination isn’t exactly as advertised. In the post-apocalyptic road movie, that seems to be the norm. Either you don’t get to where you’re going or you do and you wish you hadn’t.

But enclosed settings work brilliantly as dystopias too. From Dawn of the Dead to The Mist by way of I Am Legend, there are any number of post-apocalyptic narratives that play out as sieges. If there’s anything more terrifying than being on the run, it’s wanting to run and being trapped.

When I was writing The Girl With All The Gifts, I was aware of a sort of paradox right at the heart of it. The first third of the book takes place in a very enclosed, even claustrophobic setting – an army base in the rural heartland of an England that’s full of monsters and pretty much devoid of people. The protagonist, Melanie, lists for us the places she knows, “the cell, the corridor, the classroom and the shower room”, and we realise from what she says about them that her whole experience of the world is limited to those four locations.

But for that very reason, she doesn’t see herself as enclosed, still less imprisoned. If you’ve never seen the world, you don’t miss it. If anything, you’re more inclined to cling to what you know. Melanie is ironically grateful for the protection of the “big steel door” that marks the limit of her little world.

So at some point, I knew, I had to have her step through it and reflect on its meaning from the other side. I had to take her out on the road. Otherwise we (I mean me and the reader) would spend the whole novel exchanging knowing looks over her head.

I wasn’t sure, as I was writing, how it would play – to have such a big break point about a third of the way through the story and have everything, relationships and expectations and power dynamics and assumptions, change along with the setting. It could have been like putting Henry Winkler on those water skis. But I don’t think it was. Allowing Melanie to see the outside for the first time, and allowing the reader to see it through her eyes, putting the meaning of it together from the point of view of someone who takes nothing for granted, actually led to some of the most powerful scenes I’ve ever written.

Which maybe tells us nothing, at the end of the day, about road movies. But I think the point Roland Barthes makes about our desire for security is a powerful one. Many stories, maybe the majority of stories, either take us on a journey to a safe haven or expel us from one or allow us to live in one temporarily, knowing it’s got to end. And we respond equally strongly, as readers, to the narrative of utopia and the narrative of exile. Possibly because all of us (all of us who’ve reached a certain age) have known both of those conditions, and been defined by them.