How to write a book to film adaptation simultaneously

“For the first time ever I was writing the same story in two different media at the same time.”

I was a comics writer before I was a novelist, and a novelist before I was a screenwriter. Although actually I was scrabbling at the edges of all three of those forms before I got a handhold on any of them. I just knew I wanted to write – and what sort of stories I could write. As far as media went, I wanted to work in pretty much all of them. Stories are stories, right?

I’m not quite so blasé these days. I’ve got a sort of league table of media that I can work in and media I definitely can’t. I love prose, TV and movies, comics, and I’ll probably always want to have feet in all those camps (if I run out of feet, I’ll borrow or rent some). But I turned out to have no skill at all for radio, and games writing was a nightmare I’m still trying to wake up from. As Clint Eastwood said in Magnum Force, a man’s got to know his limitations.

There’s one particular pleasure, though, that you can only experience as a writer in multiple media – the pleasure of adaptation. I’ve been lucky enough to be commissioned several times to do comic book adaptations of novels and movies, and once to do a movie adaptation of another writer’s novel. In each case, I had a blast.

With the story structure already in place, the creative process and the creative challenges are very different from the ones you face when you’re making something entirely new. What you have to do is to dismantle the story – break it down into its component parts – and then think about what each part is doing. I’m not just talking about plot points, I mean characters arcs, themes, even key lines of dialogue. You do this because it’s not possible, ever, simply to move a story into another medium scene by scene, the way the town of Springfield was moved in that Simpsons episode by putting all the houses on wheels, driving them a mile down the road, and putting them down again in the same configuration of streets.

Okay, it is possible to do that, but it’s usually a bad idea. Every medium has its own native vocabulary, or palette, or whatever you want to call it. Its own biases. Things it does brilliantly well and things it can scarcely do at all. So when you adapt, you’re finding different solutions to the same set of narrative problematics. You’re making the story talk in its own voice but in a different language. And if you do it well, and if you’re lucky, the original writer will still recognise his or her progeny despite the pork pie hat, rah-rah skirt and Groucho Marx moustache.

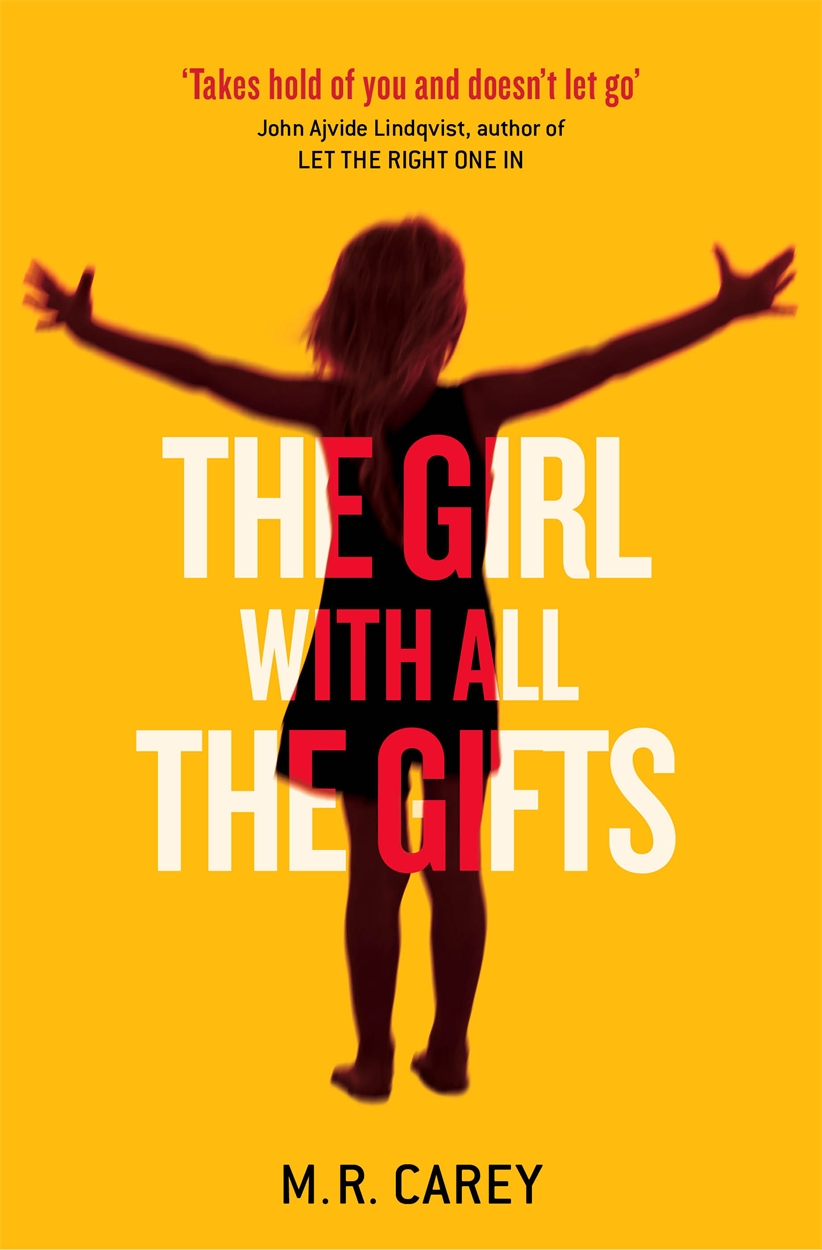

When I was writing The Girl With All the Gifts, an opportunity came up that was completely new to me. An opportunity that was – well, probably not unique, but I’d be willing to bet fairly rare.

Girl started life as a short story, Iphigenia In Aulis, which I wrote for a US anthology edited by Charlaine Harris and Toni Kelner. The original short runs to about 10,000 words, and it covers the same ground – with some very big differences – as the first quarter of the novel. It has an ending, and the ending makes sense. But I knew there was more to the story and I was determined to revisit it. I didn’t know where, or how, but those were just details.

At that time I was occasionally hanging out with a small cabal of TV and movie producers and one director. At one of our get-togethers the talk turned to apocalypses, post-apocalyptic worlds and the way those tropes are usually handled in movies. I showed them Iphigenia, and asked them if this was possibly a new way to sneak up on some of those tropes.

At the same time I was tugging at the sleeves of my Orbit editors, saying – in effect “Hey, doesn’t this short story look like it fell off the front end of a novel?”

And I got lucky. Twice. Orbit commissioned the novel, under the working title The Girl With All the Gifts, and my friendly cabal got some money together for me to write a screenplay.

Which meant that for the first time ever I was writing the same story in two different media at the same time.

That could just have meant that I imposed the logic of a novel onto a movie, or vice versa, but that didn’t happen. The people I was working with on both versions were too good to let it happen, and they brainstormed with me through a short but intense development process that ended up taking us to two very different places.

The novel does what novels do. It has five key characters – two women, two men and a young girl – and at one time or another it aims to present the point of view of every one of the five from the inside. At least one of them is a monster, but they’re all people too, and you need to understand what drives them in order for the story to work. Ultimately, I think, you have to forgive them, although that’s a tough ask in some cases.

The movie does what movies do. It remains vividly embedded with one character – the young girl, Melanie – and it lets us see the world entirely through her eyes. As a result, although it’s the same story, it will feel very different and the emotional pay-offs at the climax and coda will articulate very differently. Some elements got dropped from the story because Melanie couldn’t plausibly see or understand them. Other things got added in because from this altered viewpoint they were irresistible and inevitable.

As the writer on both versions, with the short story already behind me, I felt like I was knitting my own kaleidoscope. The characters were very clear in my mind, but I was entering their world in different ways, on different trajectories, and the story changed in great ways and small, constantly, as I made those two parallel journeys.

I believe I changed, too, but that’s an easy thing to say. The proof is in the next novel, and the next movie, if I’m lucky enough to continue working in both media.

Or maybe I’ll write The Girl With All the Gifts on ice…