Scott Lynch & Matthew Stover on THE REPUBLIC OF THIEVES and ACTS OF CAINE

Scott Lynch: volunteer firefighter, powerful Jedi, author of The Lies of Locke Lamora and the upcoming The Republic of Thieves, all round man of letters and certainly a Gentleman, not a Bastard . . .

Scott Lynch: volunteer firefighter, powerful Jedi, author of The Lies of Locke Lamora and the upcoming The Republic of Thieves, all round man of letters and certainly a Gentleman, not a Bastard . . .

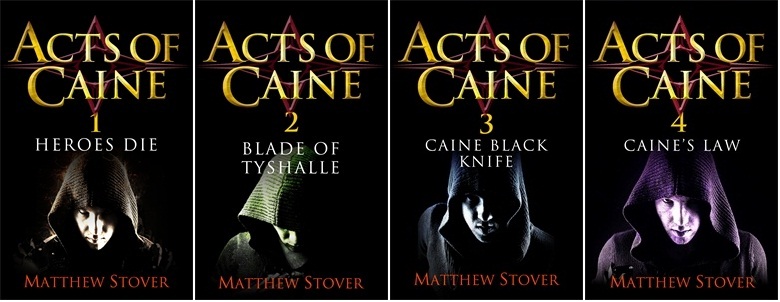

Matthew Stover: learned student of arcane martial arts, competitive drinker, author of the “heaping plate of kickass kickassery” that are the Acts of Caine fantasy novels . . . and also a very powerful Jedi . . .

Matthew Stover: learned student of arcane martial arts, competitive drinker, author of the “heaping plate of kickass kickassery” that are the Acts of Caine fantasy novels . . . and also a very powerful Jedi . . .

SO WHAT HAPPENS WHEN THESE MIGHTY FORCES COLLIDE?!

Read on to find out!

Matthew Stover: Okay, first: how soon can I get an ARC of The Republic of Thieves?

Scott Lynch: Be down at Pier 36 at midnight. Look for a man with a copy of yesterday’s Beijing Times under his arm. Offer him a cigarette. If he declines, say “Which way was the dolphin swimming?” Then follow his directions precisely. Bring a flashlight and a set of hip waders. Good luck and godspeed.

MS: Despite the first Gentlemen Bastards novel being titled The Lies of Locke Lamora, it seems to me that Locke and Jean are dual protagonists, true partners rather than hero and sidekick. While this is not unusual in other genres (especially police procedurals, for example), in ours they’re pretty thin on the ground. The only truly legendary fantasy dual-protags that spring instantly to mind are Fafhrd & the Gray Mouser, and they are explicitly portrayed as linked by mythic destiny (“Two halves of a greater hero.”) Locke and Jean, by contrast, are bound by human friendship and deep loyalty – more Butch & Sundance than F&GM.

So I’d like to get your thoughts on what inspired their relationship, and why you chose to write them this way. Were they always to be dual protags? Did Jean start as a sidekick and grow in the writing? Is there something about their friendship that has Super Story Powers?

SL: You’re making me peer back through the hazy mists of memory, man. But the honest truth is that Jean was decidedly a less fleshed-out character, initially, very much vanishing into the ensemble. His role grew in the telling, until I realized that he wasn’t just a foil for Locke but the essential foil. I grasped the benefit of having a sort of external conscience for him, another intimate perspective on Locke that would enable me to sort of hover nearby without peeling back too many layers of his mentation. For all that he’s the protagonist, we don’t spend too much time with unfettered omniscient access to Locke’s thoughts in that first novel; I wanted to express his feelings more through his actions and the responses of those around him than by writing something like, “Locke was sad now.”

You can use a matched pair of major characters to hurdle some inelegant narrative devices. They can narrate to one another through conversation in a way that would be sheer infodump if we were in one of their heads, for example. You can use their dialogue to reason through chains of events and lampshade potential problems without halting the action.

Last but not least, I think there’s a certain dynamism to their pairing that comes from the fact that it’s a humanistic relationship. There’s no magic, no destiny, no prophecy binding them. They’re in the same boat we all are in real life. We get by with a little help from our friends.

MS: And is Sabetha going to be Etta Place?

SL: Nah, different narrative arc entirely. Sabetha’s a stone cold professional crook since her early days, same as Locke, very much of the life and not looking to leave it. She’s not the type to vanish into the hazy margins of the story.

MS: The very first chunk of your fiction I ever read – on your Livejournal page, if memory serves, before you sold the book – is the scene from The Lies of Locke Lamora where the young Jean picks his way through the Garden Without Fragrance on his way to his first lesson in blade combat, then meets his teacher.

From the first line – “In the House of Glass Roses, there was a hungry garden.” — to the last, which I won’t quote, as that might deprive some readers of the pleasure of discovering it on their own, this is an immaculate goddamn piece of writing. The implicit metaphor – in essence, depicting blade combat in terms of a narrow, twisty path through a garden as beautiful as it is lethal – is so effing good I still haven’t forgiven you for it.

Can you say something about that scene specifically? Where did it come from?

Or just, y’know, how do you do that?

SL: Flattery will get you everywhere, or near enough to it. I started paying serious attention to my writing around the time I was 15-16, and the first, shall we say, instructional curriculum I ever crossed paths with was the cyberpunk/Turkey City Lexicon school of thought. I was reading everything William Gibson had written at that point, and I was deeply affected by the notion of the “eyeball kick,” the telling detail that hits so hard it sticks with a reader for years. I wanted to bring that sense of sharp, clean, killer prose and images into a fantasy setting. I still do, though not with the fervent single-mindedness of my teenage self, but I suppose that must have been where it started. Create a meaningful moment in a place that arrests reader attention… I was hungry to do it, desperate to do it. I was not particularly pleased with my life by the time I was in my mid-20s, and I was at that frustrating juncture in a writer’s development where you’ve figured out just enough to size up the box you’re stuck in. I was punching the walls and feeling them give but I couldn’t see daylight yet. I think that’s when you either give up or you sweat blood until you make a breakthrough. Well, I sweated blood and that piece of writing is what came out of it.

The Garden Without Fragrance was an outgrowth of my private exhortation to make Camorr rich in details and vivid weirdness. I didn’t want the gardens and towers and buildings to be the same damn things we’ve been seeing for half a century or more. I didn’t want my characters hanging out in Potemkin villages of the mind.

Now, if I could ask a question… it’s about your Overworld and the things that you do with it. This risks our little chat turning into a mutual appreciation society, but what the hell. What’s always amazed me about Overworld is how it’s a callback to the inherited landscapes of literary fantasy over the years, as well as a means for reflection on acting and roleplaying games, as well as a fruitful source of social and political questions—the issues of colonialism and exploitation, secret intervention in foreign affairs, the co-mingling of big business, government, and entertainment into one gestalt boot, stomping on a human face forever and selling the results to the masses at a huge profit—I mean, damn, Matt. You’re doing seven or eight things at once with the place. It’s not just rich in detail, it’s rich in narrative uses. So the question is, chicken or egg? Did you have the notion of Hari Michaelson before you had a world for him to struggle in, or did you have a world that was looking for a viewpoint to explore it?

MS: The truth is, the various narrative uses of the Overworld/Earth/Studio axis are the only things about the setting that interest me at all. The familiarity is a deliberate strategy; I want my readers to feel like they’ve seen these places before, in hopes that they’ll pay attention to anything unexpected.

Let me put it this way: I grew up in a small town in the Midwest, and lived most of my adult life in Chicago. Recently I spent a year in Florida, much of which was spent wandering about in awe at ospreys and alligators, jacarandas and banyans and royal palms and flowers all year round. Now, if someone had plopped down a completely alien plant into that ecosystem – say, a saguaro cactus – I wouldn’t have been more than mildly interested. I might have said, “Huh. A cactus.” I’d have just assumed it belonged there somehow. If, on the other hand, I were walking down my block in Danville, Illinois, and came across a saguaro in my old backyard, my reaction would be less “Huh” than “Holy sh*t!”

Overworld (and Earth, and the Studio) were created largely, if I recall, because I’m inordinately fond of Lost Earthman stories, from John Carter of Mars to Thomas Covenant the Unbeliever, and because I had become profoundly bored by the Ordinary Man Forced to Discover Inner Badass plotline (I was pretty sure nobody was going to do it better than Donaldson already had). I wanted to write about someone who was already a badass – a professional badass, in fact. And I wanted evoke the experience of playing a truly immersive RPG, without ignoring the ugly implications of what it would mean if the imaginary world in which our characters adventure isn’t imaginary. All the rest of the themes you mention above are really just emergent properties of my attempts to tell these stories as best I can.

I do like your concept of Gibson’s eyeball kick, though, even though I think I go about it a little differently. My version can be found in the Prologue of Heroes Die.

SL: While we’re at the intersection of emergent properties and prior design, can we talk about the uses of violence in your work, the aesthetic of violence? I’ve still never read anything quite like it. You don’t flinch from anything; it’s bold, bloody, gruesome, and explicit stuff, but it’s not empty or gratuitous. In fact it’s strangely humane. You received a satirical review many years ago from Dave Langford, in one of his very rare perceptual and comedic misfires, where he totally failed to grok that you weren’t merely popping eyeballs because you’re some kind of ignorant maniac. Your world is the opposite of a consequence-free environment; fights scar people visibly and invisibly for life. Where did this come from? When and where did you start shaping your fictional violence to have it both ways; to be so vivid and yet so weighty? Were there distinct design influences, or did you look up from your keyboard one day with a look of dawning surprise on your face?

MS: Was that Dave Langford? As I recall, the review was signed John Grant. [Yeah, that’s right: I REMEMBER EVERY WORD. I’M STILL LOOKING FOR YOU, GRANT! And when I find you – speaking of violence – I may snap a towel near your butt in a locker room. Or whatever the UK equivalent of that might be. Perhaps I’ll tweet something cutting about your fashion sense.]

At the risk of sounding like the aforementioned maniac: Of course violence scars people for life. That’s what I like about it.

My approach to violence is the same as my approach to every other element in my fiction. I just want to write it well. I feel an obligation to write it well. If I were a moralist (which I emphatically am not) I would say I have a moral duty to write as deeply and vividly about every subject I take on as my abilities and understanding permit. Falling short of greatness is no sin for any writer; there’s only one Shakespeare, one Tolstoy, one Twain. We have only the gifts we have been given. But failure to employ our gifts in service to our craft is unforgivable.

To write well about anything, I believe you have to recognize, and be able to touch on, all of it. The more truth you can keep in your head, the better your writing can be. I believe you can write well about love only if you never forget loss, heartbreak and betrayal – but loss, heartbreak and betrayal only have power if you also understand the sudden thrill of hope and lust and the whirl of mutual passion and all the idealized liberating sillinesses that make love irresistible in the first place.

I admit to being fascinated by violence – but I’m fascinated by all of it, all its forms and flavors, from the earliest sparks of toddlers roughhousing to the myriad damages we inflict on each other, and ourselves, to the very end of our lives. When I like it best is when it rings most true. I can’t always get that pure ring – with all its harmonics of hypnotic rage, exhiliration, dread and terror – in my own work, but I always try. If I can find a way to touch on guilt and regret and lingering pain, so much the better.

If you’ll forgive me the vulgarity of quoting myself, I think this conversation from Caine’s Law captures a lot of what I’m talking about. It’s from the chapter “Scars and Scars,” and it takes place in the clinic waiting room where the seven-year-old Hari Michaelson is waiting to find out if his mother is going to die from being beaten into unconsciousness by his father.

He stopped and shook his head, and I could tell he was making a face even though I wasn’t looking at him. “Just one thing, kid. One thing and I’ll leave you alone, okay?”

I didn’t answer because I was looking at his hands.

He sat forward on his elbows, the crutch leaning on one shoulder, hands dangling between his thighs. Which was kind of funny, because that’s exactly how Dad was sitting, but his hands didn’t look anything like Dad’s hands, which were wide and strong and hard as a brick; when he’d start in on me, he’d knock me down without even trying. Without even making a fist. He was working on the docks, and we were still eating okay, and it seemed like he was stronger every day. Stronger than people are supposed to get. Dad’s hands were scabbed and scarred and rough with callus, but they still looked like hands.

The old guy’s hands looked like hammers.

Not deformed or anything — he still had fingers and stuff — but they were covered in scars and some kind of weird stripe of skin across the knuckles and along the sides, skin that was dark as old bruise, thick and rumpled until you couldn’t even really see his knuckles at all. There might not even have been knuckles under there — even when he made a fist, all you could see was that the patch over the joints behind his first and second fingers was thicker and darker than the rest.

His hands were made to hit.

“Ugly, huh? That’s what happens when guys like me get old.” He turned them over so I could look at the scars and calluses on his palms too. Looked like his fingers didn’t really work too well anymore; they were crooked and stiff and bulged at the joints. “It’s a little late for me to take up guitar.”

I felt like I ought to say something, and even though I knew I shouldn’t even be talking to the old guy, I didn’t want to be mean. All I could come up with was, “You sure have a lot of scars.”

“Yeah. You too.”

I didn’t have any scars, not like his, just some nicks and cuts from fights after stickball and stuff. He was making fun of me. “Making fun of a kid is an asshole move.”

I didn’t know exactly what an asshole move was, except that the older kids said that when you were mean to somebody for no reason.

“I’m not teasing you, kid. There’s scars, and there’s scars.” He sounded so serious, and so sad, that I looked up at him, and his eyes were extra- shiny, like they were a little more wet. He shrugged and he coughed and he looked down. “These on my hands here, they’re one kind . . . well, hell, look here for a second.”

He twisted around and tugged the collar of his tunic down off his neck, and he had a real scar on his shoulder, jagged as a lightning bolt, rippled and weirdly smooth and white as spit.

“Wow.” I couldn’t take my eyes off it. “How’d you get that one?”

“Guy hit me with an axe.”

“For real?” I could just barely imagine it. “That is so cool!”

“Not at the time.”

“He could of chopped your arm off!”

“Except he was aiming for my neck. Whatever. But look—” He held his arm out and kind of twisted his shoulder in a little circle to show that everything still worked. “That’s one kind of scar. It’s there mostly just to remind you something happened. Where he broke my collarbone here? It’s stronger than the bone on either side. A lot of scars are like that. They heal back tougher than they were before.”

“Cool.”

“But if, like you said, he cut off my arm instead . . .” He shook his head. “That’s another kind of scar. You can live through it and learn to work around it and whatever, but for the rest of your life you’re gonna be a little bit broken. Or a lot.”

I got the idea, but I didn’t get what it had to do with me, and I said so.

“Not all scars are on your body, kid. But some of them leave you broken just the same.”

MS: So in answer to your question, I guess my personal aesthetic of violence is an emergent property of my work after all. It’s an emergent property of trying to get it right.

SL: Oh, hell, speaking of getting it right, regarding the Dave Langford/John Grant thing… after a bit of research, I see it is in fact John Grant’s Infinity Plus review from April of 2001, in which he quotes a parody he’d written with Langford. Now, the fact that Grant used the parody as supposedly illustrative of Blade of Tyshalle just underscores to me that he missed the point of your work by a mile, but it’s absolutely true that it wasn’t Langford’s review. So, my earlier comment about it being a “perceptual and comedic misfire” on Langford’s part is solely due to mis-remembrance on my part and I retract that description utterly; there was nothing wrong with the parody in its original context. My bad.

Now, I think we might be running out of time, so before we sign off I just wanted to say a few final and shamelessly unobjective things. Matt, your work set the bar for me when I was trying to learn how to even start a novel, let alone finish one, and although I’m sure you’d brush it off in person with that gruff humility of yours, I owe a great deal to you for your patience, sharp discussions, and generous encouragement. Thank you. I hope the Acts of Caine sequence finds the eager and lasting new audience it thoroughly deserves.

Scott Lynch is the author of THE LIES OF LOCKE LAMORA and RED SEAS UNDER RED SKIES (both available now) – and THE REPUBLIC OF THIEVES (released in October 2013).

Matthew Stover is the author of the Acts of Caine novels. The whole series is now available digitally, with Book 1 HEROES DIE currently at a promotional introductory price. Find Matthew Stover on Facebook here.