Happy Birthday Arthur Conan Doyle!

With THE RED PLAGUE AFFAIR (UK|US|ANZ) released so close to the birthdate of Arthur Conan Doyle (that’s today!), and its two Victorian sleuths owing much to Sherlock Holmes (after all, which fictional detectives do not?) we asked the author, Lilith Saintcrow, to tell us a bit about Doyle’s influence on her work.

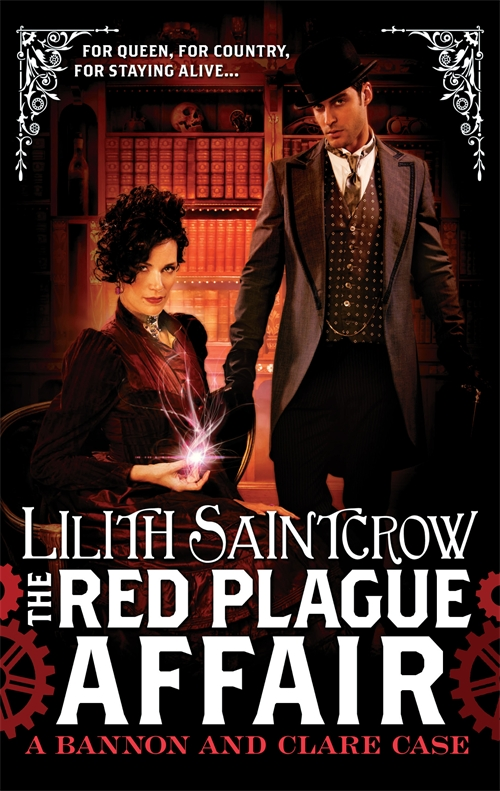

THE RED PLAGUE AFFAIR is the second of Bannon and Clare’s adventures and the follow up to THE IRON WYRM AFFAIR. Listen to the audiobooks here.

For a long time, I didn’t even know Sherlock Holmes existed. Instead, I loved another boy.

His name was Leroy “Encyclopedia” Brown.

I had two battered, ancient Encyclopedia Brown collections when I was a kid, probably from some garage sale or another. Most of the stories have receded into the mist that is my bad memory for everything before I was 20, but I remember a particular story where Leroy figured out an ambulance was the getaway vehicle because the stupid criminals put someone in it feet-first.

I was completely enchanted by the idea that a regular kid could, just by observation, change the course of events. This seemed a superpower anyone was capable of acquiring, with enough stubborn persistence and attention to detail. I mean, flight and superstrength are pretty badass, but I think most kids start suspecting neither are truly available outside their imaginations pretty early on.

I am not sure when I first began to suspect that my dear Leroy was an homage to someone else. It was probably at the point that Young Sherlock Holmes blazed into my consciousness, and I immediately marched into the library and started looking for “based on the stories of.”

Imagine my surprise upon meeting Holmes and Watson, two middle-aged men decidedly less attractive to the twelve-year-old girl I was. Arthur Conan Doyle’s prose style gave me a little difficulty, but much less than Shakespeare and only a little more than Louisa May Alcott. Plus, there were murders. Chases. A network of street kids bringing information. Cocaine. Music. Horses.

Irene Adler. Devouring them whole, I thought, who could resist these stories?

Most superheroes seem to exist to tell us who we could be if a blessing with teeth descended upon us. Sherlock Holmes, however, told me (despite Doyle’s regrettable but completely of-his-time misogyny and classism) that there was a brand of superhero that didn’t rely on radioactivity, aliens, or anything other than determination to know. Young Leroy Brown and old (to me, then) Holmes crystallized a fundamental lesson of art for me – to create, you must first observe.

You cannot hope to transform yourself, the world, or life if you first do not study it carefully.

If there was ever anything of Brown or Holmes I didn’t think I could achieve, it was the unerring instinct for which small piece of information would prove useful. I still don’t have it, but the attempts to arrive at a framework where I could have granted me what small amount of perspective I’ve gained so far. Life is not as neatly-arranged as stories can be, and gathering knowledge is a far easier thing than giving each interrelated piece its proper weight.

And so I arrived at writing Archibald Clare, part homage to Brown and Holmes (and their doughty creators), part rueful acknowledgement that it wouldn’t be very comfortable to live with such a person, and part fascination with the research into how people make “rational” choices – and how our choices may not be as rational as we like to think they are.

I still sometimes think fondly of the “Encyclopedia” Brown stories and, more often, return to Doyle’s lean-faced detective, and of course I saw the first Holmes movie with Robert Downey Jr and Jude Law. Now what I think on isn’t the superhero quality of knowledge or the instinct for the right piece of knowledge, but the tiny details in every story, where the writer, despite him- or herself, acknowledges that living daily with Holmes would be a task indeed.

It makes me wonder if my childhood crush on the idea of Leroy Brown ever truly went away. It makes me wonder if he ever grew up . . . or if Holmes did. In the end, Holmes gave the world Leroy Brown, and both of them gave a scab-kneed twelve-year-old girl the idea that her own powers of observation and perspective could be sharpened enough to be a weapon and a defense.

I am grateful for that, and will be the rest of my life. It is, if you will pardon the term . . .

. . . elementary.

~Lilith Saintcrow