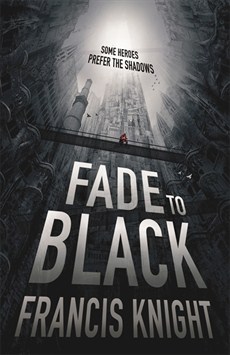

The challenges of building a vertical city

While world-building a city is an exercise in imagination, it’s always preferable, I think, to make sure you’re grounded in at least the basics of reality.

It’s possible to make buildings that can support many, many levels, so why not a city that can do the same? It takes a little extra forethought and planning perhaps. In the case of Mahala, it didn’t start off meaning to grow up, that’s just the way it happened. They ran out of room sideways, so they began building up. While this is fine to start with, just building as and when, at some point things are going to start to collapse under their own weight. Not to mention other considerations, such as “what do you do with all the waste?”.

So at some point in the past, well before the story of Fade to Black starts, a bright mage-king decided it was time to sort it all out. A superstructure was grafted on to what already existed and gave a backbone for more and bigger buildings. As Mahalians are well known for their inventiveness and ingenuity, it wasn’t just any old superstructure – the steel was strengthened to withstand almost anything. Archive details are hazy, but it seems likely that magic was involved in this – in those days magic was involved in everything. The only thing the superstructure couldn’t withstand, so it turned out, was mages. But never mind, the resulting Slump made a handy dumping ground for bodies, especially when space for crypts was at a premium.

So at some point in the past, well before the story of Fade to Black starts, a bright mage-king decided it was time to sort it all out. A superstructure was grafted on to what already existed and gave a backbone for more and bigger buildings. As Mahalians are well known for their inventiveness and ingenuity, it wasn’t just any old superstructure – the steel was strengthened to withstand almost anything. Archive details are hazy, but it seems likely that magic was involved in this – in those days magic was involved in everything. The only thing the superstructure couldn’t withstand, so it turned out, was mages. But never mind, the resulting Slump made a handy dumping ground for bodies, especially when space for crypts was at a premium.

A second problem was light – once you go up far enough, light is at a premium at the bottom. That same thoughtful mage-king made sure that even the poor sods far below his sun drenched palace got at least a minute of daylight a day by the cunning installation of lightwells and mirrors to bounce all that light around, and I’m sure everyone was jolly well grateful.

A third, and more pressing, problem is waste. There’s a lot of people who can be crammed into a city and they produce a lot of waste, if we want to be polite about it. With no space outside the city to just dump it, and not wanting disease etc to run rampant, the Stench was born. Bucket lifts (or more sophisticated ones for the nice people who live at the top) take the waste down to the Stench, where an ingenious series of vats, bacteria and the unluckiest people in the city turn it into a relatively clear water that’s allowed back into the watercourses below where fresh water is taken in. There are, naturally, some solids left but these at least no longer attract flies when they’re shunted over to the Slump.

Lastly, moving around. When you’re a hundred levels up, going all the way to the bottom to cross to the next building is less than optimal. Hence a tangled series of walkways that criss-cross the chasms. For your personal safety, nets are provided underneath, just in case. Try not to bounce though. More solid streets, bolted onto the sides of buildings, act as storefronts and access to houses, while a main thoroughfare, the Spine, twirls its way up from the very base of the city all the way to the highest spire at Top of the World.

Lastly, moving around. When you’re a hundred levels up, going all the way to the bottom to cross to the next building is less than optimal. Hence a tangled series of walkways that criss-cross the chasms. For your personal safety, nets are provided underneath, just in case. Try not to bounce though. More solid streets, bolted onto the sides of buildings, act as storefronts and access to houses, while a main thoroughfare, the Spine, twirls its way up from the very base of the city all the way to the highest spire at Top of the World.

Once you’ve all this in place, then you’re all set for your vertical city and all that remains is to name the various pieces. Sadly for Mahala, while they are known for their inventiveness when it comes to machines, mechanics and architecture, they are sadly lacking in imagination regarding naming them.