The Monster in the Mirror

Hardcore horror fans are sometimes dismissive of “creature features” – horror narratives that build their scare tactics around a monster. Obviously there’s a very respected classical canon of monsters (vampires, werewolves, zombies, demons . . . ) that sit close to the heart of the horror genre and partially define it. But then there’s a host of other beasties that are exiled to the outer darkness – or the Black Lagoon, 40,000 fathoms, outer space, the Korean sewer system, wherever it was they came from in the first place.

I can see the distinction, to be honest. You look at a vampire (sparkly or not) and you think horror. You look at the spiky cactus beast from The Quatermass Experiment, or the lolloping mutant in The Host, or Godzilla stomping on a toy Tokyo, and you think sci-fi. Or depending on your tastes, maybe you think “that tea isn’t going to make itself . . . ”

There’s a deeper distinction to be drawn, though. It concerns our relationship with the monster and the reaction that it draws from us. Creature features are predominantly about spectacle, and they probably share more DNA with thrillers than with horror stories. They can be scary, but it’s a fairly uncomplicated fear. The fear of being eaten, say, or having your head ripped off. Monsters in horror have the potential to scare us or challenge us in different ways.

I’d been thinking about this on and off for a long time, but what really brought it home to me was an evening a few months back when I watched The Host with my daughter, Lou. This is the Korean monster movie directed by Joon-Ho Bong, by the way, not the 2013 sci-fi flick with Saoirse Ronan. Mild spoilers for that movie follow in the next paragraph, so beware.

Lou really enjoyed the build-up – the creature’s early appearances, the abduction, the hunt, all that stuff. But when we got to the climax, where the three protagonists join forces to bring the monster down, she was furious and disgusted. I mean, really outraged. She felt, very strongly, that the monster was an animal, and that whatever it had done it had done out of instinct rather than malevolence. Its actions had no moral dimension, and Lou flat-out hated being invited to celebrate its suffering and death.

I found myself defending the movie, which I like a lot, but I was forced to admit that Lou had a solid point – and that brought home to me the elusive factor that unites the monsters in the horror canon. Which is that they’re us. They’re all variations on a human template, and the effect they have on us ultimately depends on that fact. You look at them and see yourself in them, which means that the fear they inspire includes a large chunk of recognition.

I don’t mean to be prescriptive about this. There are a hundred ways to do great vampires, great zombies, great werewolves. But they often dance around specific, not-very-well-buried correspondences that complicate and intensify our reactions. Vampires at rock bottom are all about sex, and the physical and moral contamination that can come with sex – diseases and guilt and sin, all unsettling both in their own right and as metaphors for each other. The transmission of a curse by means of a nightly visitation, the bite and the feeding, the vampire’s irresistible hypnotic wiles, these things are part of a coherent iconography. The classic vampire narrative plays out as either a seduction or a rape, and either way it works on fears about sex and sexuality that run very deep.

Werewolves are sexual too, but in a different and more tangential way. Colm McCarthy, who directed the amazing werewolf movie Outcast, argues that the werewolf myth draws on the traumatic experiences we all undergo at puberty; specifically, the feeling that our body is changing in ways we can’t anticipate or control. Unexpected and uneven growth and the sprouting of hairs in places that used to be smooth translate in the werewolf mythos into a more radical bodily transformation – and, as with vampires, into a profound loss of control over our own animal appetites. Outcast, by the way, interprets this process in a way I’d never seen before, and Colm’s werewolf is easily the most disturbing I’ve ever seen.

I think zombies attack our sensibilities from two different directions. They’re still recognisably, undeniably us, but they’re two other things besides – corpses and animals. They remind us simultaneously of our origin among the beasts of the field and our destination under it. That’s why the moments in zombie narratives that really punch me in the guts are the moments when we’re made to see the spark of human consciousness and awareness still alive in the rotting animal carcass. In Land Of the Dead, for example, when the zombie musicians loiter in the bandstand clutching the instruments they can no longer remember how to play. Or in the first episode of The Walking Dead, when the zombie woman keeps coming back to the door of the house where she used to live and staring at it through the night, unable to break the link to her past even though she no longer understands it. I’d like to add Zombie In A Penguin Suit, too, although what affects me most there is the poignant reminder that this dead-eyed creature used to have a human existence and a human context. Comedy as tragedy.

As I said earlier, I don’t want to suggest that this is a law or even a formula. I just think it’s a potent dimension in a lot of horror stories that feature monsters: that we’re forced to confront, in the monster, aspects of our own nature that are disturbing, frightening or hard to acknowledge.

The seminal horror text, for me, is Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. In that story, the monster only becomes a monster through the outrageous neglect and cruelty of his creator, Victor Frankenstein – and their unequal struggle becomes a lens through which we view both parent-child relationships and the relationships between the haves and have-nots in our own society. The pains we inflict become the scourge that destroys us. We are always, in the end, our own monster.

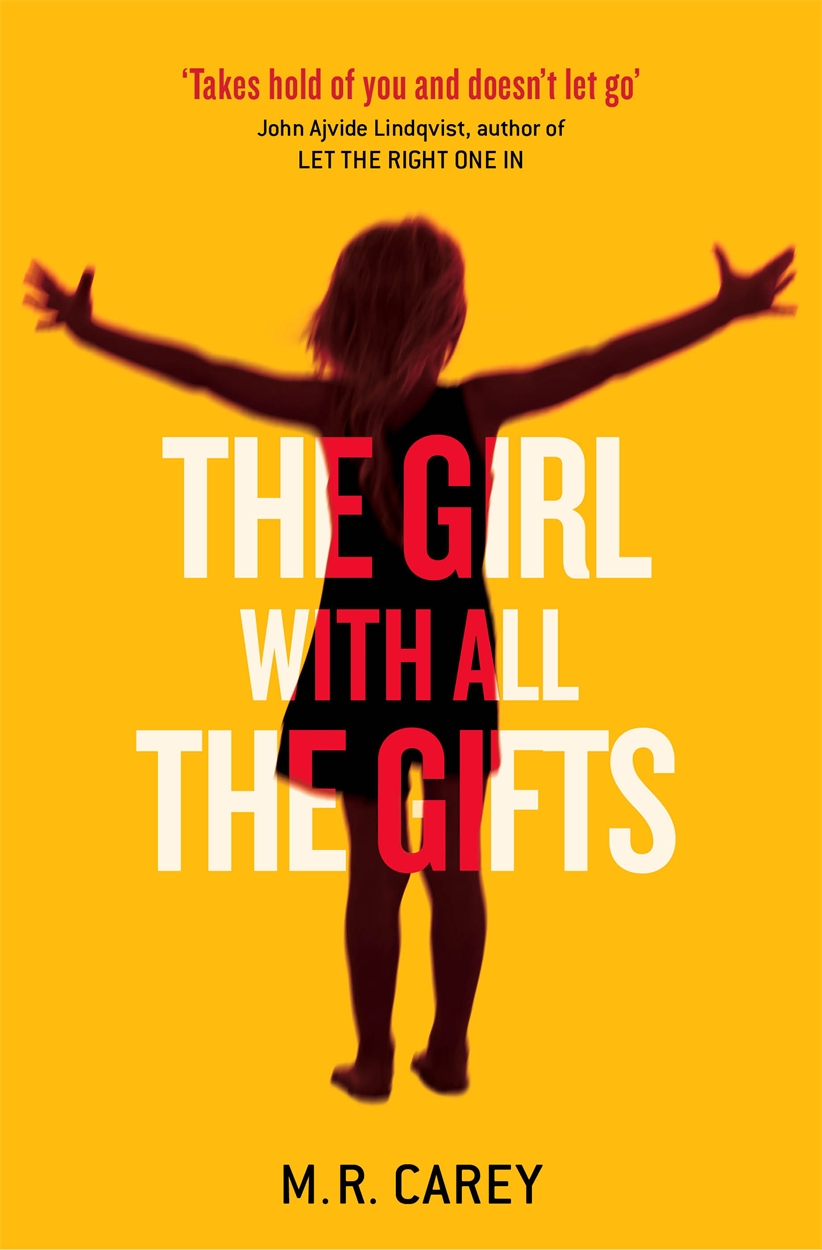

I approached The Girl With All the Gifts with these thoughts simmering in my mind. It contains two monsters, of different kinds, but both are intended to be mirrors and touchstones for the reader. And the writer, for that matter.

As Pogo Possum once said: we have met the enemy, and he is us.