He Said, She Said

I decided pretty early on, when I first was playing with the elements of what would become the universe of ANCILLARY JUSTICE (US | UK | AUS), that the Radchaai wouldn’t care much about gender, and wouldn’t mark people’s gender in their speech. Not because I wanted the Radch to be any kind of prejudice-free utopia–far from it.* But because I (somewhat naively) thought it would be interesting.

It actually took me a while to realize what a can of worms I was opening. To some extent, I’m still realizing it. But at first, I was faced with a purely mechanical problem–how to portray a society that just didn’t care about gender, while I myself was using a language that required me to specify gender at every turn. It’s pretty much built into English to specify a person’s gender, even when it’s is totally irrelevant to the topic at hand, and it’s difficult–not impossible, mind you, but difficult–to talk for very long about a person without mentioning their gender. **

At first I tried just asserting that Radchaai didn’t care about gender, and then using gendered pronouns throughout. I was unsatisfied with this. (And unsatisfied with those first couple of novels, which are in a drawer hidden from view until further notice. Only a few people have seen them.) I became more unsatisfied with it the longer I considered it, in fact. In the end I decided to pick one pronoun (at least for the sections where, presumably, my narrator is speaking Radchaai) and stick with it in all cases.

Often people assume (wrongly) that “they” as a singular pronoun isn’t “proper” English. It is in fact entirely grammatical and available to use. It’s most often used to refer to a nebulous “someone” whose ambiguous existence makes gender difficult to guess, but there are an increasing number of recent examples of singular they used in cases where gender is known and/or not a simple matter of either/or.*** I could have used it for Ancillary Justice, but it didn’t feel right. I’m not a hundred percent sure why.

I could have chosen any one of the ungendered pronouns that have been proposed over the years. This also would have been entirely workable. And inclusive–though we’re used to thinking of gender as an obvious either/or, male/female, really things aren’t always that clearcut. On the minus side, using any of those pronouns would have made getting into the story difficult for readers unfamiliar with them, at least at first. This is not a reason to never use those pronouns, of course, but I admit it was a consideration for me here.

I could have gone with the old standby, “the masculine embraces the feminine,” and just called everyone “he.” This is, in fact, the choice made by Ursula K LeGuin when she wrote The Left Hand of Darkness (Which is awesome, and if you haven’t read it, it is my considered opinion that you should.) Years later, she expressed some dissatisfaction with having made that choice. It made the Gethenians seem to be all male, which they were not, and failed to convey their non-binary nature.

There was, as I saw it, one more possibility–I could use “she” for everyone. This would have the same disadvantages as using “he” with the advantage of not being the oh-so-common masculine default.

I thought about all these options. They all had advantages and disadvantages. The most inclusive choices would also be harder to read. The choices that would be easier to read would potentially have the effect of making the universe seem as though it was populated entirely by men or by women. And whatever choice I made, I was going to have to stand by it. Because I knew the pronoun thing would jump right out at the reader. I had to decide up front if it was something I would be willing to compromise on, and if so how or how far. I had to know why I’d made that particular choice, because I was quite sure someone was going to ask me why, or even try to talk me out of it.

In the end I went for readability. And for “she.” When my narrator was speaking Radchaai, anyway. When she speaks another language, if it uses gendered pronouns she uses them as appropriate. Or attempts to. Because really? She’s not very good at guessing, outside of cultures where she’s spent a fair amount of time and learned a fair amount about local customs.

Problem solved. Pretty much. Except, my solution didn’t only fix my mechanical problem, it suddenly made the fact that there was a default visible. The thing about defaults is, they’re automatic. Most of the time you don’t even think about them. They just seem quite obvious and natural. Using an unusual default, particularly one that’s close to but not exactly like the usual one, really highlights the fact that there’s a default there to begin with. And suddenly neither my solution nor my initial problem seemed simple at all.

I didn’t start off meaning to examine how the use of gendered pronouns shapes our thoughts about the people around us, really I didn’t. But then, isn’t that one of the things science fiction is for, what it excels at? Imagining strange and unfamiliar worlds, that maybe give us a new and interesting way to think about our own?

…

*Radchaai society isn’t exactly a dystopia, either. Over time I’ve become a bit impatient with black and white, either/or characterizations.

**Yes, I know. You see what I did there.

***I’ve seen it used well in some recent short fiction.

…

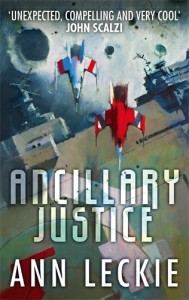

ANCILLARY JUSTICE (US | UK | AUS) is available now! Check out the book that io9 called “the mind-blowing space opera you’ve been needing“.