Elizabeth Moon on Grit vs. Glory in Fantasy Writing

By Elizabeth Moon

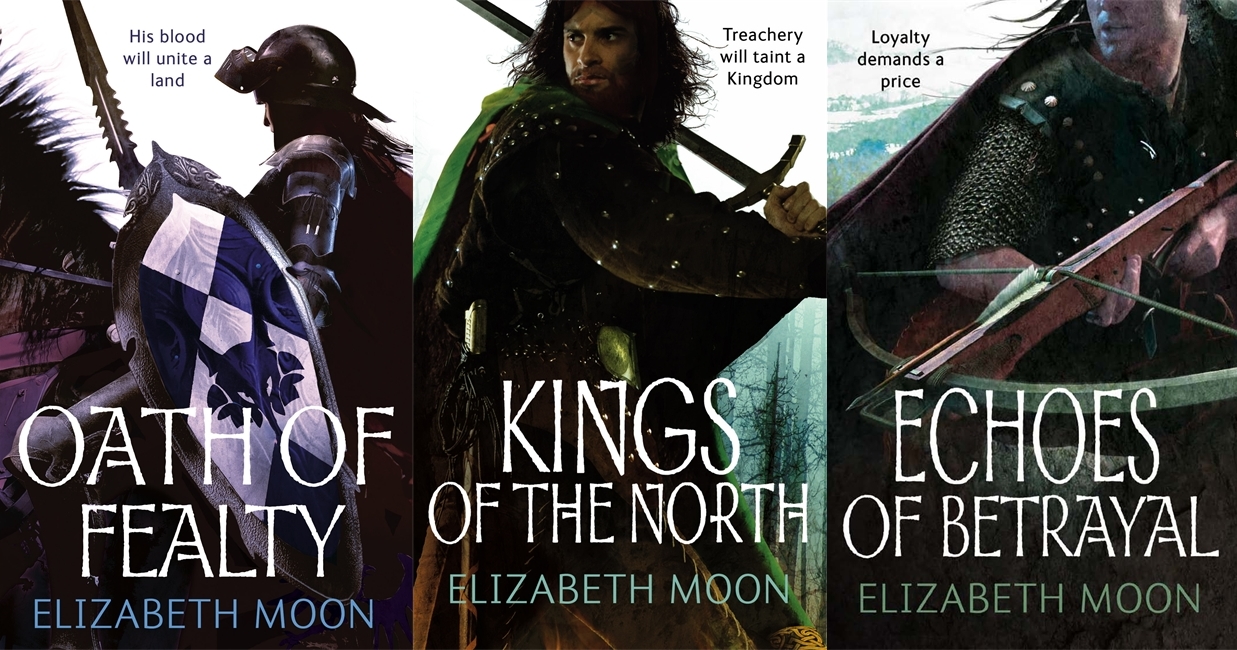

When my first novel came out in 1988, SHEEPFARMER’S DAUGHTER (UK|ANZ), some readers commented favorably on its “gritty reality.” People died in war, some gruesomely (one of a suppurating gut wound, a baby accidentally trampled, civilians made an example of by one or another mercenary force), and that included characters readers identified with as well as those they didn’t. Later in that group of books, the protagonist suffered more wounds, unjust and cruel reactions as an aftermath of “treatment” for mental invasion, and torture. Some readers were horrified that a woman would write such graphic violence; others admired an honest appraisal of the costs of both war and heroism.

Yet the point of the story was not that war is hell, that people are capable of cruelty, that violence has unexpected costs that land unfairly on the innocent. That’s common knowledge. The point of the story was how people – as characters – deal with this reality. How some become bitter, angry, resentful, and willingly participate in the cruelty. How others do not, and instead work against the cruelty – sometimes violently and sometimes by choosing to stand with victims, without resisting.

Yet the point of the story was not that war is hell, that people are capable of cruelty, that violence has unexpected costs that land unfairly on the innocent. That’s common knowledge. The point of the story was how people – as characters – deal with this reality. How some become bitter, angry, resentful, and willingly participate in the cruelty. How others do not, and instead work against the cruelty – sometimes violently and sometimes by choosing to stand with victims, without resisting.

Gritty reality has been associated, in some other writers’ works, with a determination to deny the possibility of glory – of redemption, of steadfast adherence to good, of achievement. Some even seem to believe that the good are just stupid, too stupid to realize that you have to be bad to survive. That’s not my perspective. I’ve known too many good people who were also intelligent and street-smart, surviving well without knifing everyone else in the back. I’ve known too many other people who used the “good = stupid” argument to defend their own cowardice and complicity in evil.

Gritty reality has been associated, in some other writers’ works, with a determination to deny the possibility of glory – of redemption, of steadfast adherence to good, of achievement. Some even seem to believe that the good are just stupid, too stupid to realize that you have to be bad to survive. That’s not my perspective. I’ve known too many good people who were also intelligent and street-smart, surviving well without knifing everyone else in the back. I’ve known too many other people who used the “good = stupid” argument to defend their own cowardice and complicity in evil.

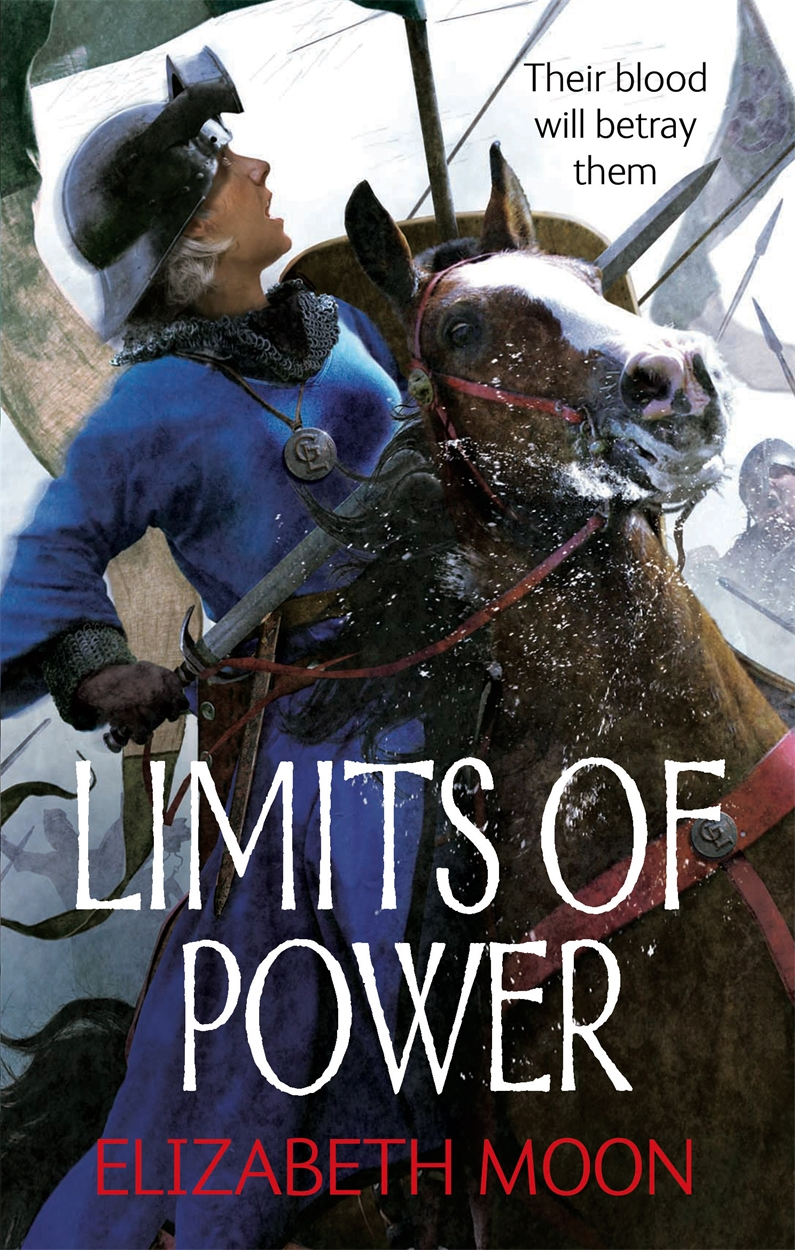

Does good win easily? Of course not. Does good always win? Of course not. Does one battle win a war, or one war win anything forever? Of course not. But I stand on the side of those who think that good can win . . . if. If what? If those trying to make things better don’t give up, don’t sell out, don’t lose hope that their efforts are worthwhile. If they learn enough about themselves to recognize where they are part of the problem . . . and then have the courage and will to change. LIMITS OF POWER (UK|ANZ) is part of a series that challenges adults – not kids becoming adults – to change repeatedly, to become more than they were.

Does good win easily? Of course not. Does good always win? Of course not. Does one battle win a war, or one war win anything forever? Of course not. But I stand on the side of those who think that good can win . . . if. If what? If those trying to make things better don’t give up, don’t sell out, don’t lose hope that their efforts are worthwhile. If they learn enough about themselves to recognize where they are part of the problem . . . and then have the courage and will to change. LIMITS OF POWER (UK|ANZ) is part of a series that challenges adults – not kids becoming adults – to change repeatedly, to become more than they were.

So when I write the gritty realism scenes – the bloody scenes, the painful scenes, the betrayals and lies and horrors – it’s not to say that this is all of reality. That life is nothing but cut-throat, back-stabbing competition where love and trust and honor are a fool’s terms. No. I write them because such things exist, and the only way to something better is through the dark times, when heroes show what it takes, even if they fall, to bring something better to birth. It’s never easy. It’s always hard, harder than the person who started with high ideals can imagine at the beginning. But everything gained has come from these sacrifices, large and small.

One illustration. Some time back, an old man lived alone in a trailer at the edge of a trailer park on the edge of our town. He was an alcoholic with heart trouble, retired from bartending, known to spend the day in his recliner sipping whiskey. The town considered him harmless enough – he wasn’t a mean drunk – but useless, too. The more judgmental made it clear they disapproved of him and his lifestyle.

Across the old barbed wire fence around the trailer park was a house with a few acres attached. One day the old man looked out his window and saw that the neighbor, in trying to pull a stump with a tractor, had instead pulled the tractor over backwards onto himself. Now the thing about overturned tractors is that they catch fire. So the old man ran out of his trailer, climbed the fence with some difficulty and ran as fast as he could to the tractor and the fire now burning.

He was out of breath, his heart pounding irregularly, certainly not as strong as he had been when young, but he did his best to help the trapped man get out from under the tractor before the fire got to the gas tank and blew up. Both of them suffered burns, but they were far enough away when the gas tank blew to survive. By then the local volunteer fire department was arriving at the scene . . . but it would have been too late for the trapped man if the old drunk hadn’t come running.

The old man needed oxygen and cardiac meds as well as treatment for the burns on his arms and hands . . . yet he sat in the local clinic, not asking for treatment, asking only about how the trapped man was doing – almost ignored, initially, because the trapped man (who had burns on his legs) was loud and demanding. He had saved a life, but he thought that was something anyone would do, just what people did for each other. Nothing special. That he was the one who had done it shocked a lot of people . . . “But he’s a drunk,” was heard more than once. So he didn’t just save a life – he taught the town (without meaning to, or even knowing he’d done it) that heroes aren’t always young and handsome, or the people labelled “good” or “solid citizens.” That anyone may have in them a hero’s heart and will. You can’t tell until the crisis comes.

The old man needed oxygen and cardiac meds as well as treatment for the burns on his arms and hands . . . yet he sat in the local clinic, not asking for treatment, asking only about how the trapped man was doing – almost ignored, initially, because the trapped man (who had burns on his legs) was loud and demanding. He had saved a life, but he thought that was something anyone would do, just what people did for each other. Nothing special. That he was the one who had done it shocked a lot of people . . . “But he’s a drunk,” was heard more than once. So he didn’t just save a life – he taught the town (without meaning to, or even knowing he’d done it) that heroes aren’t always young and handsome, or the people labelled “good” or “solid citizens.” That anyone may have in them a hero’s heart and will. You can’t tell until the crisis comes.

If I used this incident in a book, there’d be some gritty realism – the crackle and roar of flames, the paint blackening on the tractor, the greasy black smoke, the old man staggering as he ran, desperate to get there in time, the trapped guy screaming for help as the flames reached his legs, clawing at the ground, remembering the live ammo in his jeans pocket, the smell of burning clothing, blisters rising on skin . . . and more. I would include the ingratitude of the trapped man and his loud complaints from the moment he was safe. For him, it was all about himself. But the fear and pain both men felt isn’t the point, nor the bad behavior of the person who was stupid enough to hitch a tractor to a stump and then pull the tractor over. The point is an old man whose life had been, to many, a complete failure . . . and that moment of decision when he got out of his recliner and ran toward the fire. That moment when townsfolk had their assumptions overturned and saw the old man as a very different person, and were confronted with the fact that age, health, and social status had nothing to do with heroism.