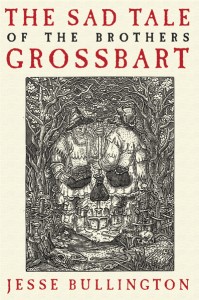

A History of the Reality of the History of the Grossbarts: Part 1

I first encountered Hegel and Manfried Grossbart as a child in an old book my parents picked up at a garage sale—Trevor Caleb Walker’s Enter the Nexus, Black Monolith. Not realizing what a rare find this century-old edition was, my parents gave me the glorified chapbook, thinking that Walker’s thrashing, inept verse was intended as limericks for children, a bit like the copy of Wilhelm Busch’s Max and Moritz that I so adored. At that age I did not even realize Walker was intending poetry and thought it was simply a bizarrely written series of short stories about graverobbing brothers being unkind to man, woman, and beast. I certainly did not appreciate the volume’s value, and so it went the way of so many old horror comics and paperbacks—worn out and abandoned after a few summers, and entirely forgotten by the time University beckoned.

I first encountered Hegel and Manfried Grossbart as a child in an old book my parents picked up at a garage sale—Trevor Caleb Walker’s Enter the Nexus, Black Monolith. Not realizing what a rare find this century-old edition was, my parents gave me the glorified chapbook, thinking that Walker’s thrashing, inept verse was intended as limericks for children, a bit like the copy of Wilhelm Busch’s Max and Moritz that I so adored. At that age I did not even realize Walker was intending poetry and thought it was simply a bizarrely written series of short stories about graverobbing brothers being unkind to man, woman, and beast. I certainly did not appreciate the volume’s value, and so it went the way of so many old horror comics and paperbacks—worn out and abandoned after a few summers, and entirely forgotten by the time University beckoned.

Then came Professor Ardanuy’s history class, and who should I see on the syllabus but my old friend Trevor Caleb Walker and a pdf of his epic poem. Approaching the professor after class, I mentioned having owned a copy growing up, and before I could even tell him that I was looking forward to the class I was whisked off to the bearded man’s office, a strange shine in his eye. He grilled me for the better part of an hour, and when I confessed to not knowing what had become of my copy of the text he turned the color of an old campfire’s coals and drank straight scotch from a coffee mug. I was told in no uncertain terms that were I able to produce the book my success in the class was assured. When I tactfully told him I would not be able to scour my old room until the holiday break he poured himself a second mug, and said in a conspiratorial tone,

“Dunn’s coming for Christmas, my boy. We mustn’t disappoint Dunn.”

I was, in a word, unnerved. I went to see my academic adviser about dropping the class but she had already left for the day, and so I went home and called my mother. She confirmed my suspicions that the tattered tome had been lost or thrown away a decade previous. Having gained some idea of the volume’s worth from Ardanuy’s unabashed hunger for the thing, I went to bed bummed to have lost a treasure but not terribly concerned for my academic future.

The next morning I went to my adviser’s office straightaway, only to be informed that due to some issue with capping of class sizes and prerequisites for a History major and something called the Don Johnson Initiative I would be unable to drop Ardanuy’s class without jeopardizing my scholarship. That my adviser had a large, unopened bottle of scotch with a skeletal elk head on the label did not escape my notice, nor did the fact that this was the same whisky Ardanuy had been pounding the day before. An undergraduate had precious little recourse in those dark days, unfortunately, and so I was trapped.

Over the course of the semester my classmates dwindled, dropping one after another like desiccated leaves from a dying oak, until midway through the term I was the only student still attending class. When I asked Ardanuy about this he became irate, his knuckles going ivory around the ornately carved cane he carried everywhere despite being spry as an athlete half his age. Every class he asked about the book, and every class I stalled him, sticking to my story that I would not be able to search my childhood possessions until after the semester.

I learned a great deal from Ardanuy, indeed, few scholars could match his passion, and I soon discovered that everything I thought I knew about the Grossbarts was wrong. They were villeins who questioned the status quo of serfdom, not villains out to make a mark. The professor would, during the classes when he had more than a cup of his Scottish coffee, reenact some of the Brother Grossbarts’ more impressive battles, and to this day my arms are striped from his cane. I fell under the old man’s spell, and one fateful day when I took the professor up on his standing offer of a cup of coffee I confessed to having lost the book.

Ardanuy did not rage, as I might have expected. On the contrary, all the color and emotion seemed to leave him, and he became as some blank golem. “Oh dear,” was all he would say, “oh dear.” And then, as I was leaving, “Dunn won’t be happy.”

Of course by this time I had become intimately acquainted with Dunn’s scholarship, the man’s Holy Beard, Holy Grail being the core text of Ardanuy’s class. That Dunn had written the introduction for Ardanuy’s own book on the Grossbarts was a fact that was reiterated every time the subject came up, which was daily even as the semester came to its conclusion and my meetings with Ardanuy were nominally stripped of their academic worth—I did not return home, but stayed on as his assistant over the winter break. My nervousness at Dunn’s imminent arrival to give a lecture was only compounded by Ardanuy’s grave demeanor in the days leading up to the event, and the news that I would personally be retrieving the great man from the airport. Ardanuy refrained from accompanying me.

All my trepidation evaporated upon meeting Heer Dunn, the kindly fellow appearing every bit as soft as Ardanuy was rough, his sideburns trim, his goatee long and downy. As I carried his bags down to the car he mentioned the Walker volume that Ardanuy had told him I owned, and I told him the truth of the matter.

“Ah, is the way with mothers, yes, throwing away the preciousness of youth,” Dunn bobbed his head knowingly, his cane tap-tap-tapping across the parking lot. The gilded walking stick bore more than a passing resemblance to Ardanuy’s, and this similarity was made all the more obvious when he suddenly jabbed me in the back of the knee with it. I fell, and before Dunn’s bags had crashed to earth beside me the great man was battering me with his cane and bellowing in Dutch.

I might have perished from the assault if a bearded shadow had not appeared from between the cars brandishing a cane of his own, and the battle was joined. By the time I had wiped away the tears enough to see that Professor Ardanuy had rescued me the two men were embracing, canes hanging limp, a strange, identical laugh coming from their throats. Then they turned to where I lay, their eyes glittering in the light of a streetlamp, and Ardanuy said,

“Heer Dunn, may I introduce my research assistant, Jeffrey Wellington.”

That even after four months of daily interactions Ardanuy could not get my name right bothered me far less than the welts rising on my legs and the cruel hardness to their faces.

“Mecky little Jeffrey is making his introductions poorly,” said Dunn. “Tut tut.”

“He’ll make it up to you,” said Ardanuy, and there might have been fear on my professor’s face. “He’ll make it up to both of us.”

“Yes,” said Dunn, straightening up. “Yes. I am double-checking Rahimi and Tanzer’s attendance at Baton Rouge, and both are committed.”

“We’ll be there by dawn,” Ardanuy nodded vigorously.

“Baton Rouge?” I struggled to my feet, legs as wobbly as my mind from excruciating pain and the mention of the hated revisionists Tanzer and Rahimi, a pair of academics who had irrevocably besmirched true Grossbart historicism. “I thought your lecture was here, tomorrow, and—”

Dunn raised his cane and I went quiet. “Lecture is canceled, little Jeffrey. We are going to debate with fellow scholars.”

I pretended not to notice the pearl-handled pistol Ardanuy slipped Dunn as we got into my car and drove away from Tallahassee, toward Baton Rouge and a reckoning with the revisionists.